Batterie recycling

What about the advanced recycling fee that is levied on batteries? Are we importing our batteries on the grey market? The rumour was doing the rounds that we had not paid any advanced recycling fees. I checked with Inobat, which is responsible for collecting the fees. The situation turned out as follows: We were simply one of the first companies to use lithium batteries for our vehicles and it was simply not yet regulated how Inobat wanted to deal with it. A short time later it was decided that we would also have to pay these fees and so everything was settled. I was interested to know where the batteries were I was interested to know where the batteries were recycled and how the material that went into the

production of our batteries was recovered. Together with Claudia Fesch, our contract manager, I visited the only recycling plant for batteries in Switzerland in Thun. We saw a very impressive, huge blast furnace operated by the company BATREC. In it, all the batteries were burnt and a little bit of material could actually be recovered. But mainly slag was produced, which had to be put into final storage somewhere. We were both horrified by the sheer waste.

Some time later, I sat together with Claudia, Rolf Widmer and Marcel Gauch from EMPA in Nuremberg at a seminar on the latest battery developments with a focus on the ageing of lithium batteries. The evening before the event, we were sitting in a nice restaurant and during dinner the following idea came up: Surely the best way to recycle batteries is to simply take them apart in the same way as they were assembled before. That sounded simple enough - but was it? We wanted to know! A little later, Marcel Gauch got in touch: he had been approached by an environmental technology student. This student was looking for a diploma thesis on lithium-ion batteries. He had written a term paper on 2nd life batteries and had already opened and taken apart batteries in his own cellar.

Couldn't this be the start of an attempt to recycle our batteries? The modalities were arranged and shortly afterwards Olivier Groux introduced himself. He had the ideal qualifications for the task.

For the task: before his studies, he had trained as a chemical laboratory technician. He was familiar with all the chemical substances that were presumably in a battery cell. He also knew a lot about electrical engineering and mechanics. By the end of the thesis, Olivier had proved to us that the theory worked. In addition, he had accidentally found a method to dissolve the active material, graphite, in the copper (anode) and iron phosphate in the aluminium (cathode).

I was thrilled! Olivier was rewarded with the highest grade and started a new job as an energy consultant for the city of Bern.

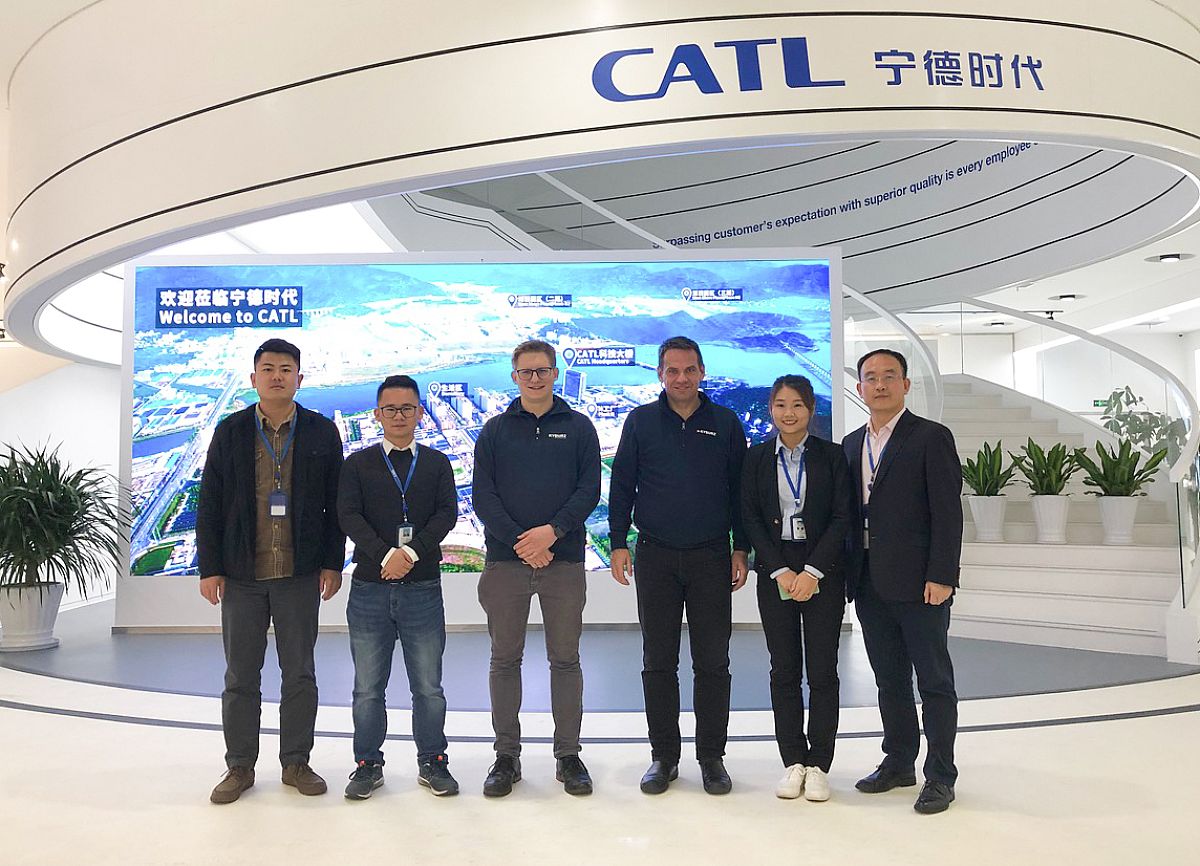

After that, unfortunately, his email addresses were no longer valid, and it took me some time to track down his address: I offered him a job if he developed a battery recycling system for me for the batteries we used. Olivier didn't need any time to think. A budget was negotiated to develop and build the plant, and Olivier got started. Together with EMPA, he worked out the process. He travelled to China and visited many battery manufacturers to study the production process in more detail. One day, a call came from China. Olivier was on the phone. He also visited our battery manufacturer, from whom we had been buying our cells for many years. There was something strange: he had seen the production plant, but it had been converted to a different chemistry. My ears pricked up. Batteries are a key product for our vehicles. We agreed that he should extend his trip by over a month and that I, together with Philipp Heim, would also come to China to talk to the battery suppliers. Since Olivier's visa had expired, he travelled to Tokyo to work in the home office and wait for his new visa. Meanwhile, Philipp and I had also arrived in China, and together we visited another 5 battery producers. We learned a lot, including how the whole battery market in China is structured. The construction of batteries was seen as a key element in China and was therefore promoted by the state. For us, it meant that we could get high-quality lithium-ion batteries for a very reasonable price. For the manufacturers, it meant that if they met their production target, they got more of the government subsidies. So it was positive for both of us. Each of the manufacturers had just built a new production plant, we often heard of several hundred million euros being put into a production plant. At that time, nobody was interested in recycling the raw materials. The biggest battery producer we visited was CATL. They had over 30,000 employees - a whole city. We got to see some laboratories and realised that CATL was certainly the most advanced in their development. Since then, CATL has been our new main supplier.

We returned to Freienstein full of joy. Not only had we found a new excellent battery supplier, we had also learned a lot about the production of batteries. Knowledge that Olivier was able to put to excellent use in his recycling process. All this knowledge was shared with EMPA, and together they created a poster showing and explaining our recycling process. One day, Olivier asked me if I would mind if EMPA and we presented this poster together at a competition to show a novel process. Of course, I had nothing against it. After all, I wanted the knowledge to spread. EMPA entered the competition and won first prize. The win made us happy - but it also had its downside. We had given a research contract to EMPA Dübendorf, but none to EMPA in St. Gallen. The management intervened, and so we had to place an order in St. Gallen as well. The deserved first prize cost us a considerable sum.

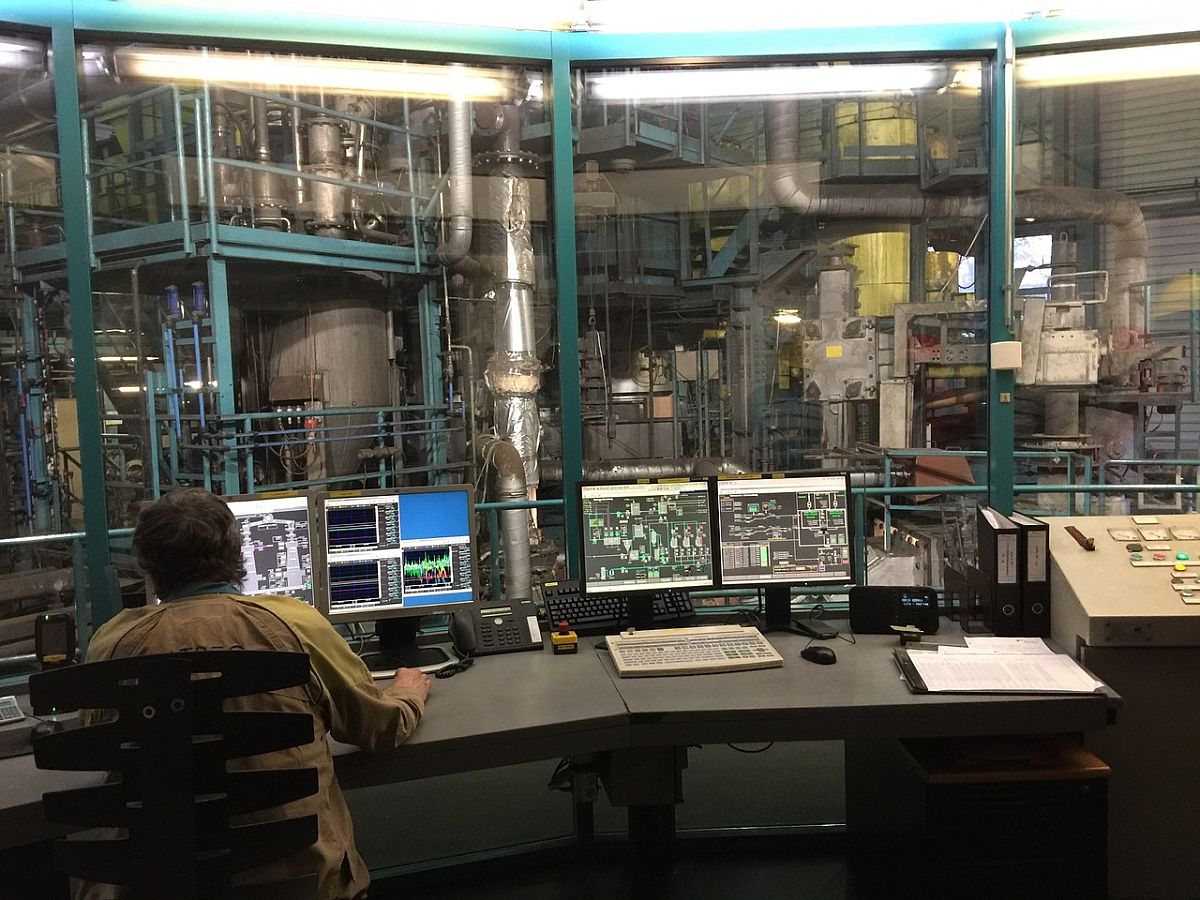

Towards autumn 2020, the Circular Economy Symposium we organized took place in Freienstein. At the event, I wanted to present our recycling plant in a press conference. We had the actual machine built by the Welthaupt company in Appenzell. Was everything finished on time? All participants said yes, but the closer the deadline came, the more hectic the work became. The Welthaupt company needed support and one of our employees worked for months at the company without any red tape in order to build the machine on time. As usual with such a project, time was running out. I insisted that before the actual press conference, the machine was already set up and available for a photo opportunity. The managing director of Welthaupt wanted to make this possible, but said: He would have to dismantle the whole machine afterwards and transport it again to his workshop in Appenzell to finish building it. No, that couldn't be the idea either. I didn't want to burden the people involved in the project with additional difficulties in the decisive final phase. The employees of Welthaupt could continue building and our photographer had to be very flexible.

Shortly before the conference, the machine was set up and run in. Samuel, the managing director of the Welthaupt company, was the operator. He knew the machine best. The photographer got his pictures and the documents could be produced just in time. I saw the machine running for the first time on the day of the press conference, as did Marcel and Rolf from EMPA, and we were all very excited. Seeing the battery cells disappear into the machine and at the end of the process all the raw material was available again in pure form was the great reward for all the drops of sweat shed by Olivier Groux's team. The best thing about it all: The machine is now powered exclusively by solar energy, and no chemicals are used for the disassembly. Simple water was enough.

We deliberately did not write a process patent. We make the knowledge available to the whole world. The best possible recycling of used batteries is existential for us humans, especially in this day and age.

I learned from this:

- We always finish complex projects a few minutes before the presentation.

- Switzerland has many raw materials - processed into batteries. They just have to be recovered.

- Occasionally I am surprised by the success of a project.